Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom, because judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.

James 2:12-13 (NIV)

In recent years, the craving for social justice has spilled out into the streets with Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street, bringing the issue to the forefront and forcing Christians to decide if social justice is the same as biblical justice.

It is not.

John R. W. Stott urged Christians to remember that “man is not just a soul to be saved.” He said that loving our neighbors is worthy because they are human, they have worth, and we have a desire to serve them. As Christians, we should be concerned about their total welfare, including their community, and this concern should be expressed practically. This is a call for integrating justice with ministry.

Justice, especially social justice, is a hot topic. Dr. Matt Harmon of Grace Theological Seminary has pointed out that there is such a variety of definitions that they can contradict each other. Here is some clarity: social justice is a modern term invented and likely designed to replace, in contemporary and rational terms, the biblical justice that is now ignored as obsolete.

Christians seem to be playing catch-up with the secular world by defending biblical norms, in this case how justice applies to society, as if to show, in spite of all real evidence, that Christianity is a serious religion. The fact that justice is a foundational biblical term indicates that Christians are not wrong, even if we may have been lax recently.

The topic of social justice is a reminder of the social gospel which came from a desire within the church to emphasize the “good works” aspects of the biblical mandate. By contrast, while the social justice movement has its origins entirely outside the church, social justice has become a phrase used by Christians, especially in North America, to indicate a desire to be involved in good works, including biblical justice in the social realm. Christians inside the church who are motivated by love (or charity) have found, in social justice, a rationale for serving both God and humanity.

There is an important distinction between biblical justice’s voluntary acts of love and the institutional obligations of social justice; a distinction that apparently does not seem significant to many believers.

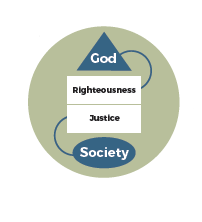

The key to understanding biblical justice is to understand that in the Bible, justice equals righteousness. Psalm 89:14 states that righteousness and justice are the foundation of your throne. Amos 5:24 adds famously, “Let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-ending stream.”

In both testaments the word for justice is often the same as the word for righteousness (δικαιοσύνη). The word is translated depending on its use. If the topic relates to God and his behavior or requirements, it is translated “righteous.” If the topic relates to society and living for god in the world, it is translated “justice.”

Righteousness and justice are two aspects of the same attribute of God. If something is righteous, it is also just. If something is just, it is also righteous. Both are in harmony with God’s character, and it makes sense that both are aspects of life we should embrace as we live in his created world.

Not so with social justice, which is divorced entirely from God and finds its basis in society. That is why it is called social justice—not society as an arena of God’s righteousness, but society as the foundational source of a definition of justice. No one would confuse ‘social truth’ with ‘biblical truth,’ but we often confuse social justice with biblical justice.

Social justice today is an expansion of John Rawls’ impactful book, Theory of Justice, in the 1950s. Social justice is a school of thought that assigns rights and duties to the institutions of society. These are government institutions that enable people to receive the basic benefits and burdens of social cooperation. The relevant institutions often go beyond the courts to include public school education, social insurance, public health, public services, labor law, and the regulation of markets to ensure a fair distribution of wealth, income, and equal opportunity.

Looking at these institutions, Christians are impacted not only by the omission of the church but by the exclusion of any reference to God having any impact on justice. The government institutions have replaced God as the source of justice and bounty, and citizens are to depend, not on God, but on the government for justice in all areas of life.

Positive Rights and Critical Race Theory

It is the job of the government to assure that all people have equal outcomes. Two related teachings are essential. First is the concept of positive rights. We are familiar with the Bill of Rights attached to the U.S. constitution. These are negative rights. We are free from interference as we talk, gather, and exercise our freedoms, including religious freedoms, and we are free from unjust invasion of our property or false accusations.

Positive rights, by sharp contrast, are rights that society provides. We are all convincedthat children have a positive right to education,

and the social safety network is now embraced as a social right. But the positive right to health care, college education, and a middle-class job exist only in the realm of social justice.

Another support for social justice is critical race theory, which not only acknowledgesthe horrors of racial slavery but states that white supremacy is the entire basis of our Constitution and history as a nation. Positive rights and Critical Race Theory are extreme, but the nightly news has stories that normalize a view of social justice that is far from biblical justice.

Aristotle helps us consider ordinary justice as we still use his categories of justice. Aristotle taught corrective and distributive justice in order to distinguish between what everyone must have the same (corrective justice based on rights) and what everyone must have differently (distributive justice based on merit). Rawls fundamentally changed those categories so that people have social justice: an inherent right to what formerly was earned by merit.

Everyone has heard of someone who was “Teacher of the Year” in a nearby school district, but who was later laid off due to severe budget cuts. Why was one of the very best teachers suddenly without a job? Not because of merit (distributive justice), but because of seniority (corrective justice)—which treats everyone the same, based on the date of hire. Even Aristotle has situations that appear to be an injustice. So did Jesus.

A Parable

Jesus told a parable of vineyard workers who were all paid a full day’s wage even though some had worked only for an hour. Those who had worked a full day complained of injustice, even though they received the full day’s wage (Matthew 20:1–15). They did not want to see what looked like “rights” (corrective) justice when they thought this had become an area of “merit” (distributive) justice. Jesus’ point was that generosity is good, and ultimately grace transcends any form of justice.

While it causes confusion, “justice” today must also bear the burden of being a popular and even overused word used as a substitute for other less popular words. For example, when people want to avoid the unpopular word “righteous,” they substitute the word “justice.” People also prefer the term “justice” as it helps avoid the personal moral and religious aspects of other words like “character.” Furthermore, the idea of justice helps us to escape personal responsibility

as we retreat into the public arena where good works no longer need to be seen as “righteous” or religious.

When wanting to emphasize the importance of “fairness” or “equity,” some people think it best to rename them as “justice” to lend moral authority to other less compelling (“fair”) or even rejected (“righteous”) concepts. There are many arenas where love and compassion motivated justice can be applied. There are realms including education, health, social needs, relief, and local development. Even the realms of corrective and distributive justice can be pursued in love,

especially where there is injustice in convicting and sentencing in our penal system.

Command them to do good, to be rich in good deeds, and to be generous and willing to share (1 Timothy 6:18 NIV).

Do not forget to do good and to share with others, for with such sacrifices God is pleased (Hebrews 13:16 NIV).

In the context of seeking justice in the social realm, James wrote, “mercy triumphs over judgment” (James 2:13). This is the equivalent of saying that grace (like mercy, but dramatically better) triumphs over justice (which, when violated, results in judgment).

High Value

Justice has high value, and the ideals of social justice are appealing. But when Christians relegate grace to a secondary status behind justice they fall into a trap that is all too common. They are tempted

to wrongly conclude that social justice for “the kingdom” is better than doing good works in the contexts of the gospel of grace and the church, even the local church.\

Phil Yancey wrote movingly of the gripping and difficult Truth and Reconciliation days in Nelson Mandela’s and Desmond Tutu’s South Africa. Yancy concludes, by focusing not on justice and not even on mercy, but, as we should, on God’s grace: “Grace means that no mistake we make in life disqualifies us from God’s love…. We live in a world that judges people by their behavior and requires criminals, debtors, and moral failures to live with the consequences….Grace is irrational, unfair, unjust, and only makes sense if I believe in another world governed by a merciful God who always offers another chance.” [1]

This is where the grace of God not only intersects biblical justice but provides the motivation and direction for such justice. We must not settle for less. We must not settle for a shrunken social justice. Social needs, especially of the oppressed, find relief through the active compassion of those who cannot separate justice from righteousness as a faith response to God’s grace. – by John Teevan

—

A long-time Charis Fellowship pastor, John Teevan is an adjunct professor in the School of Ministry Studies at Grace College, Winona Lake, Ind., where he previously was the executive director of Regional Initiatives.

[1] Rumors of Another World: What on Earth are We Missing? Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003, 222-24.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of GraceConnect magazine. Click here for more information.